|

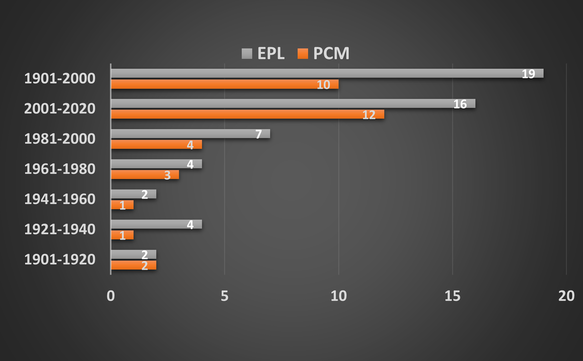

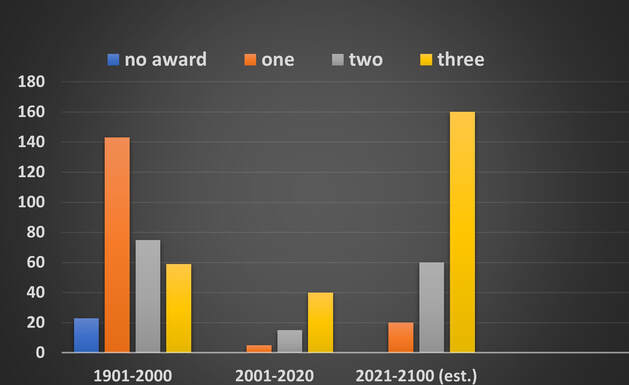

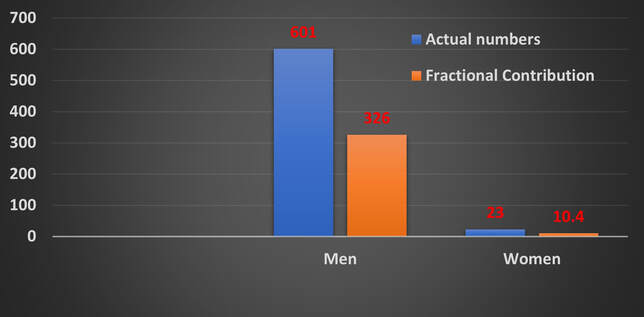

By Vijendra Agarwal The year 2020 marks the 120th year of the globally acclaimed Nobel Prizes. This October was slightly different because we were recognizing the most important scientific discoveries and inventions at the same time that we were also experiencing the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic. While cures to major diseases like coronavirus and the flu remain elusive, the vaccines under trial may be future candidates for the Nobel prize. Here’s hoping that at this time next year we will be celebrating new breakthroughs in medicine that uphold Alfred Nobel’s mission to reward discoveries that help humankind. To complement two earlier articles focusing on gender bias and overall trends in the Nobel Prizes, this article takes a more holistic view of the Nobel Prizes, with a focus on gender disparity in Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine/Physiology (PCM), and how the awards have changed over time. There are encouraging signs of a more welcoming attitude change and mindset and a growing number of women scientists making headway in the male dominated PCM fields. The number of women PCM Laureates in the first two decades of this century has already surpassed the number of women PCM Laureates in the first 100 years of Nobel history. I start with duly acknowledging the 2020 Nobel recipients and why this is a historic year for women Nobel Laureates in PCM. It is followed with a discussion about the ever-present gender gap in Nobel awards in PCM and how it is perpetuated by a growing trend in which the Nobel prize is shared among 2-3 scientists. When possible, I compare the gender gap in PCM with other awards in Social sciences and Humanities (Economics, Peace, and Literature, aka EPL). Finally, I conclude with evidence showing incremental progress has been made to close the gender gap and I describe efforts made by Nobel leadership to increase diversity among prize winners. Supporting efforts like these will be essential for improving diversity in scientific thought and invention at all levels of research. The Nobel Prizes in 2020 The 2020 PCM Nobel prizes acknowledged and celebrated a total of 8 scientists, including 3 women. Each disciplinary Nobel in PCM was shared by multiple scientists: three in Physics, two in Chemistry, and three in Medicine/Physiology, following the new trend in which the Nobel has become a shared prize. In contrast to PCM, the 2020 EPL Prizes were awarded to 3 individuals, including the sole female (Louise Gluck) in Literature. The addition of these three female winners in PCM increased the number of women Nobel winners in this field by 38% (from 8 to 11). One of these women, Andrea Ghez, received the Physics award only two years after Donna Strickland won the same award in 2018. In addition to awards won by Marie Curie in 1903 and Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963, Ghez is only the fourth women to join the Physics Nobel ranks. She was part of a team of 3 physicists recognized "for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the center of our galaxy," commonly referred to as the formation of black holes. As a physicist myself, I was overjoyed and pleasantly surprised that Ghez received the Nobel in Physics, as I had articulated the urgent need to nominate more women physicists in a 2018 article : “Wanted: More Nobel Prizes for Women Physicists.” 2020 was also the first time ever that two women, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier jointly shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for “the development of a method for genome editing." Commonly known as CRISPR-Cas9, this method is a revolutionary gene-editing tool that allows scientists to rewrite DNA and change the code of life over the course of a few weeks. “There is enormous power in this genetic tool, which affects us all. It has not only revolutionized basic science, but also resulted in innovative crops and will lead to ground-breaking new medical treatments,” says Claes Gustafsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry. A similar event had occurred only once before in 2009 when two women shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine. In recent years, the Nobel Foundation’s leaders, like secretary-general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Göran Hansson, are beginning to pay attention and discuss diversity in the Nobel prizes. Under Hansson’s leadership, appropriate measures are already underway to decrease the gender gap and increase both geographic and racial diversity. However, there is still a long way to go towards achieving diversity and gender balance, and we must continue to advocate for these changes. Closing the Gender Gap The continuing gender gap in the sciences is one of the most discussed issues at all levels in academia. The Nobel Prizes to women in PCM are representative of this disparity. Since its inception, 601 men and 23 women (including Marie Curie who won the Nobel twice in 1903 and 1911) have received the PCM awards. This accounts for merely 3.69% women of all Nobel Laureates in 120 years. To put it differently, for every year a man has won the Nobel, a woman received the award once every 5 years. Averaging out the awards over time, however, ignores that most of these awards to women have only happened in recent history. This is clearly shown in Figure 1 which charts the number of women Laureates in PCM (and EPL, for comparison) every twenty years. New efforts recognizing the need to bridge the gender gap across scientific fields may give us reason to remain optimistic. Luis Echegoyen, the President of the American Chemical Society, said, “For too long, many discoveries made by women have been underplayed and they have simply not been recognized.” Similarly, Michael Maloney, CEO of the American Institute of Physics, noted, “We have a long way to go yet to achieve gender equity in physics and a longer path yet to achieve true inclusivity and belonging in our field.” Working to acknowledge the scientific accomplishments of women scientists begins much earlier than at the Nobel prize stage, however. The stark reality of academic gender disparity is visible during tenure and promotion decisions; it permeates through most salutary awards/recognitions in later academic career stages as well. As a comparison, women Nobel winners in the EPL fields (Figure 1) have outnumbered women Nobel winners in the PCM fields almost by a factor of two (19 versus 10) between 1901-2000. However, that gap between EPL and PCM awards may be decreasing, according to data from the most recent 20 years (12 in PCM versus 16 in EPL). The gender disparity also shows up in the number of women who receive the award individually compared with those share the award with men. In PCM, 147 men received the Nobel Prize individually, but only 3 women received that sole distinction in the past 120 years: Marie Curie (1911) in Physics, Dorothy Hodgkin (1964) in Chemistry, and Barbara McClintock (1983) in Medicine. Does this mean that standards for judging the quality and merits of female scientists’ research differ from those used to evaluate men in the male dominated PCM disciplines? Our collective objective should be to ensure that gender bias is not the reason for this outcome. We must continue to ask why there are fewer individual women Laureates and why most of these women share the prize with men. The Sharing of Nobel Prizes Each Nobel Prize in PCM is often shared by two or three people, likely due to the rise in complex and collaborative science. Currently, there is a cap on the award being shared by more than three scientists. As seen in Figure 2, the number of individual awards has steeply declined from 143 in the 1900s to only 5 individual prizes in the past 20 years (note that in some years, no Nobels were awarded due to World Wars or other unavoidable reasons). Awards shared by two people have also declined in recent history, while awards shared by three people have rapidly increased. In contrast to the PCM fields, the cumulative EPL Prizes (not shown) are still dominated by sole recipients. The Peace Prize was given to 69 individuals versus 32 shared awards. Literature is almost always awarded to an individual (109) than shared by a group (4). We are likely to see more shared Prizes in EPL, however, largely driven by Economics which has an almost equal split between individual (25) and shared (27) prizes. Like PCM, Economics is more of a quantitative discipline necessitating greater collaboration. The Fractional Contribution (FC) The Nobel prize is not always shared equally between scientists who win a shared award. Fractional contribution refers to the monetary value assigned by the Nobel Committee based on an individual scientist's contribution to the group's work. It is important to consider Fractional Contribution (FC) when evaluating gender disparity in the Nobel Prizes because even though more women may be nominated, they may be recognized for contributing less to the award than their male counterparts. Improving gender disparity among Nobel Winners must involve both nominating women and ensuring that their share of the Nobel is awarded based on merit, and not historical biases. When taking fractional contributions into account, the numerical ratio of men to women awardees goes from 3.69% to 3.09%. I added up the relative contributions awarded to each male and female scientist in PCM awards shared by both men and women, and translated it into a total cumulative award number. This resulted in 326 awards given to men and 10.4 awards given to women, as shown in Figure 3. The ratio of fractional contributions (326/10.4) is 3.09%, which is 0.6% lower than the ratio of total prize recipients (601/23) at 3.69%. In other words, men receive 54% of the credit on average for each shared Nobel, while women typically receive 45%. While the Nobel Committees quantify the relative scientific contributions of each award recipient when recommending unequal splitting of the prize money, it is important to ensure that this disparity is not unconsciously motivated by historical gender bias. Concluding Remarks and Recommendations The total number of women Nobel recipients in the last 20 years is significant because it exceeds the total number of women Nobel winners in the entire 20th century, suggesting that efforts to close the gender gap are on the right path. This appears to be the case as a result of numerous statements from the Nobel leadership acknowledging the need to improve gender disparity among award winners. The media’s involvement in bringing attention to gender-bias in the Nobel awards has also helped raise awareness about inequality in academia and help accelerate this much-desired cultural shift. We close with a few final recommendations for next steps to improve equality and diversity among Nobel prize winners:

Finally, it is important to note that gender disparity is not the only issue affecting diversity among Nobel prize winners. There is a biased geographical distribution of Nobel Laureates, which may reflect some scientists’ ability and choice to immigrate to countries with greater funding for scientific endeavors. Removing the three-person cap and recognizing the diverse ways in which scientific collaboration occurs today will also help reduce bias against scientists limited by their country’s resources.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2022

CategoriesAll Amy Massack BiWeekly Roundup Danae Dodge Gabrielle-Ann Torre Indulekha Karunakaran Jeesoo Sohn Lauren Koenig Lidiya Angelova Melissa Bendayan Microsoft Molly Connell Nektaria Riso Nicole Hellessey Physics Poornima Peiris Robbin Koenig Sadaf Atarod Sarah Smith Shreya Challa Vijendra Agarwal Women In STEM Yolanda Lannquist |

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed