|

By Vijendra Agarwal

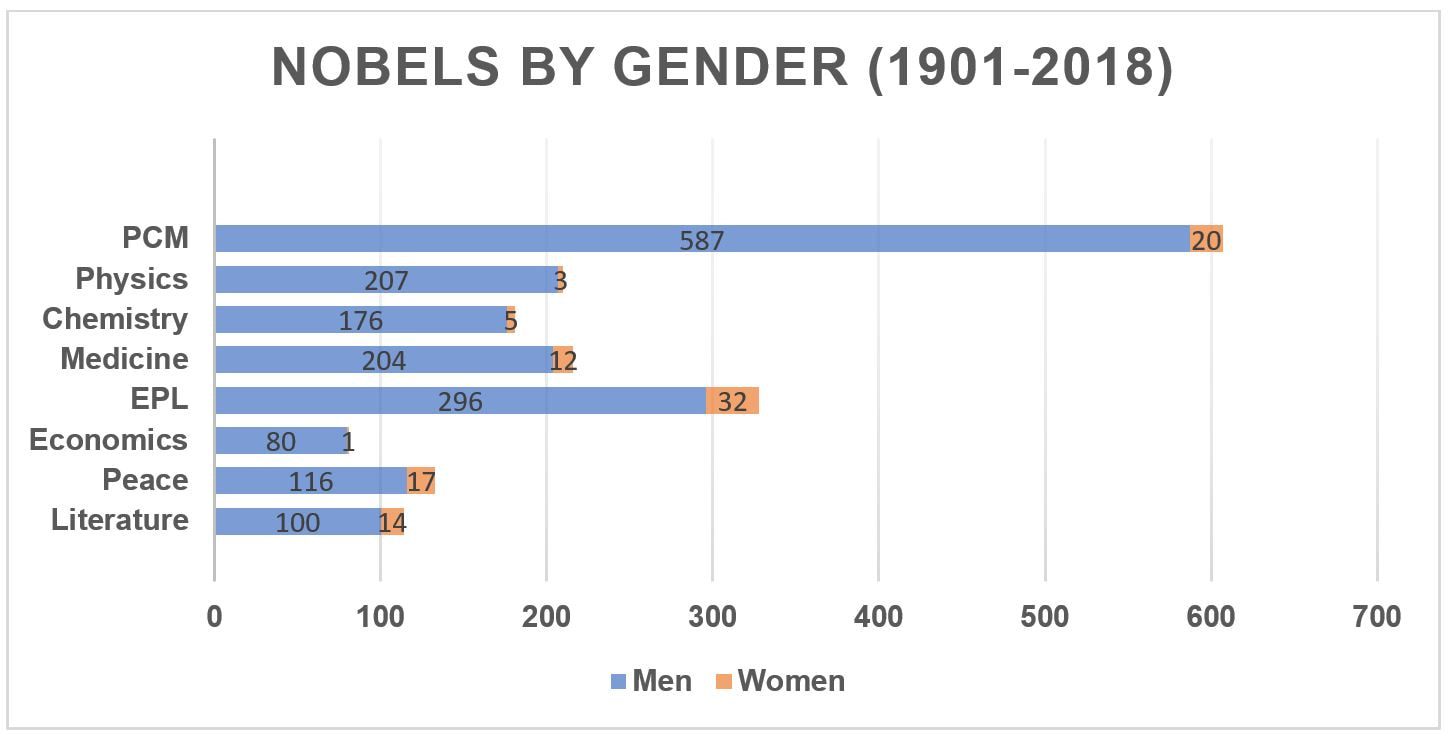

Since 1901 to date, there are 935 Nobel Prize recipients, but only 52 are women. The proportion of Nobels awarded to women in the sciences (20/607 in Physics, Chemistry and Medicine; PCM) is more unequal than in other categories (32/328 in Economics, Peace, and Literature; EPL). This October, like any other, the world celebrated the addition of 8 science Nobel laureates (including 2 women), the highly acclaimed distinction accorded to individuals for making breakthroughs in their fields. This year, there was a welcome change when a Nobel was awarded to Donna Strickland, the first woman to receive the Nobel in physics for the first time since 1963, and Frances Arnold, the first woman to receive the Nobel in chemistry since 2009. The gender disparity among Nobel Prizes is highlighted by the award announcement’s timing at the start of a month dedicated to celebrating women in science. October 10th is Ada Lovelace Day, an international celebration aimed at supporting women in STEM, and October 11 is the International Day of the girl – a United Nations effort to empower girls around the world, many of whom will become future scientists and engineers. One of the consequences of the continued Nobel gender gap is that there are fewer role models to showcase how far women can excel in a science career. When Alfred Nobel set the rules for the Prize in the late 1800s, he stated “It is my express wish that when awarding the prizes, no consideration be given to nationality, but that the prize be awarded to the worthiest person, whether or not they are Scandinavian.” Male dominance was inherent to the culture at the time and thus it is perhaps expected that there was no stipulation for gender parity. Nobel would not have been able to predict that the awards would become the “white” men’s refuge, as if women and “non-whites” were not as welcome, even when advancements in gender and racial inequities were made at other levels in the sciences. However, the discussion of racial disparity among the Nobel landscape deserves its own dedicated time and place. Several questions must be answered in order to identify the root cause and develop a remedy for this situation. Is science itself sexist? Is there a gender bias among the nominators and members of the committees at various steps of selection for the Nobles? Is there a leaky pipeline leading to fewer women studying science and fewer women scientists deserving of the prize? While the gender gap is shrinking, the culture and climate in academia is slow to change. A recent publication by the National Academy of Science highlights the issue in detail. The question we must ask is how we can accelerate the cultural shift to affect a reduced gender gap in the Nobel space. The 21st century world will be better served with women scientists getting due recognition at all levels, including Nobels. Our progress in technology and innovation may be thwarted without an equitable representation of women in STEM. The Leaky Pipeline: Undoubtedly, we have made gains in attracting more women in STEM, as seen by headlines in 2016 such as, “ Women break barriers in engineering and computer science at some top colleges.” However, the numbers drop at each career stage; fewer women complete their Ph.D. in STEM areas, and still fewer of them are hired as faculty. A recent study titled “The Prestige Gap” suggests that men are overrepresented in elite Ph.D. programs, especially in math heavy fields. It appears that many women self-select themselves out of the equation because of self-assessed ability, the environment within the program being unfriendly or unsupportive, and a culture which leads to many more women than men developing a fear of failure that prevents career advancement. This leads to further reduction of women in STEM at elite institutions, which are known to produce Nobel laureates. Many male-dominated institutions retain a culture that is a hold-out from before the 21st century, in which women continue to face challenges in being recognized and promoted at the workplace. Talking about the challenges in academia, one must wonder why the newest woman physics Nobel laureate, Strickland (at age 59), remains an associate professor (not yet promoted to full professor) after decades of research and teaching. Male chauvinism is clearly alive and well in a recent statement made by a senior scientist (Alessandro Strumia), “physics was invented and built by men." He went so far as to say that physics was "becoming sexist against men." Damaging beliefs held by people like Strumia only serve to widen the gender gap in STEM disciplines. The Historical Bias and Madame Curie: Any discussion of why we have so few women Nobel scientists must begin with Madame Curie, the first woman ever to pierce the “diamond” ceiling of the Nobel prize as early as 1903 - although not without hiccups. Today, she is the only person (not just as a woman) to hold the distinction of being awarded two Nobel Prizes; physics in 1903 and chemistry in 1911. While we must celebrate every Nobel Laureate as a great role model, Curie is a mentor par excellence. In an extraordinary gesture, Curie delayed her own studies to let her sister complete a degree in medicine. Additional sacrifices highlight her dedication to her work and also serve as a testament to how deeply rooted the “bias” against women may have been in the early 1900s. For example, she worked shoulder to shoulder with her husband Pierre Curie, and yet the French Academy of Science (FAS) did not include her name in the initial Nobel nomination in 1902. If Nobel Committee member and mathematician Magnus Goesta Mittag-Leffler did not intervene as an advocate for women scientists, history would have been very different. She informed Pierre about the situation and he, in turn, wrote to the Nobel Committee, “A Nobel Prize for research in radioactivity that failed to acknowledge Marie's pivotal role would be a travesty.” Unfortunately, the Nobel award did not end all bias against Curie. The FAS later voted against Curie’s induction in FAS (by two votes) for fear of her breaking up their “men’s club.” It took until 1962 for Yvonne Choquet-Bruhat, a former student of Marie Curie, to become the first woman elected to the FAS. Curie’s personal life was also subject to intense scrutiny. A media circus attacked Curie and her daughters at their home when news leaked of her alleged involvement with physicist Paul Langevin, one of her husband’s former students, four years after her husband’s death. The Polish-born Curie was accused of home-wrecking a French family, which fed into xenophobic tensions of the time. There are certainly many situations today that show that this behavior continues; the media lens is often hyper-focused on the women named in the situation, no matter their culpability. Despite all the odds and turbulence in her personal and professional life at this time, Curie won the second Nobel in Chemistry in 1911. She mentored her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie, who also received the Nobel in Chemistry (alongside her own husband) in 1935. The family dynasty of Curie has the distinction of holding 5 Nobel medals in total. This mother-daughter pair were the only women scientists in the Nobel space until 1947, when the first American, Gerty Theresa Cori, received the Nobel in Medicine. A woman of extraordinary talent, courage, and perseverance, Curie opened doors for other women because of her many accomplishments. However, the progress since then has been painfully slow and the gender bias is still pervasive. The Deserving Women Deemed Unworthy of the Nobel: It is hard to quantify the number of women of extraordinary talent that may have been overlooked by the Nobel committee. However, science historians and fellow scientists have made no secret that dozens, if not hundreds, of women contributed to the discoveries and research for the betterment of mankind. Due to a confidentiality agreement in which nomination data is kept secret for 50 years, it will be a long time until we know how many and how frequently women were nominated for the prize. Some scientists, however, have slipped through the cracks and entered the sphere of public knowledge: a) Physics: The physics community will forever miss people like Mildred Dressehaus (died 2017), rightfully dubbed as the Queen of Carbon. Her research work inspired two other Nobel prizes- 1996 Chemistry and 2010 Physics, but possibly her nominator(s) and/or the Prize awarders were not inspired enough to make her a Laureate. Vera Rubin’s (died 2016) pioneering work on the theory of dark matter was overlooked while the 2011 Nobel Prizes honored three men instead. Likewise, Chien-Shiung Wu’s (died 1997) experimental work led to her exclusion from the 1957 Nobel Prize, awarded to two men. A retired UCLA physicist Nina Byers called Wu’s absence from the 1957 Nobel, “outrageous” and the science historian at Brandeis, Pnina Abir-Am, did not mince words when she suggested that Wu’s ethnicity also played a role. How unfortunate that these extraordinarily talented women are now part of “unrealized” Nobel history. b) Chemistry: Katherine Blodgett is known to have worked very closely with her mentor Irving Langmuir on single molecule surface layers. However, only Langmuir received the Nobel in 1932 and Blodgett was never nominated for the honor. Their joint surface layer research, commonly known as Langmuir-Blodgett films, is part of this author’s professional history and the key focus of his dissertation. Another notable scientist, Lise Meitner, was nominated 48 times for the Nobel (19 times for chemistry from1924-1948 and 29 times for physics from1937-1965) for her work on nuclear fission of uranium. Ironically, her work was never acknowledged by the committee during all those years, while her collaborator Otto Hahn was awarded the 1944 Nobel in chemistry. c) Physiology or Medicine: A trailblazer for women scientists, Esther Lederberg closely worked with her husband, Joshua Lederberg, on antibiotic resistance. However, like many, she was not credited for the Nobel in Medicine with her husband in 1958, which he instead shared with two other men. Joshua acknowledged that the 1953 Eli Lilly award in Bacteriology he received should have been shared with his wife, but he chose not to mention her when he accepted the Nobel in 1958 (they remained married until 1966). A final, and well-known example is that of Rosalind Franklin, a British biophysicist who paved the way for our understanding of DNA and RNA. Later, the Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded to three male scientists in 1962 but excluded Franklin. It is important to note that although Franklin died in 1958, she could have been nominated posthumously for the Nobel at that time, prior to the changes in Nobel policy in 1974. The examples above highlight that the collaboration between men and women helped make these scientific achievements possible. Why then were only men awarded and the women unrecognized? Why were all but 4 Nobel Prizes awarded to women scientists shared with men, as if the women were not capable of recognition individually? Some of these instances can be attributed to the “Matilda Effect,” an unethical practice of ascribing women’s accomplishments to men. In other cases, these patterns may be due to plain and simple gender bias, rules that prevent no more than three people from sharing the Prize, and/or the policy that no nominations can be awarded posthumously. In my informed view, the gender bias, perceived or real, cannot be completely ruled out, but going forward it can and must be corrected. The Student-Supervisor Collaboration: Many noteworthy outcomes in the sciences are offshoots of research conducted by graduate students under the guidance of their thesis supervisor. However, not all thesis work alone, typically limited by university mandated graduation time, leads to seminal discoveries worthy of the Nobel within a student’s tenure at that university. Such collaboration needs a special mention in light of two extraordinary occurrences in the recent weeks. We focus on two women physicists making history in 2018. The finest example of due recognition of student-supervisor collaboration is Donna Strickland and her supervisor Gerard Mourou. They will equally share one half of the Nobel Prize money (the other half goes to Arthur Ashkin) for their seminal work on the method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses. The tale of British scientist, Dame Susan Jocelyn Bell Burnell, a postgraduate student at the University of Cambridge in 1967, and her supervisor, Antony Hewish, had a very different outcome. It is no secret that both scientists discovered the pulsar through a joint effort, but only Hewish shared the 1974 Nobel Prize in physics (alongside another man). This may have been due to the effects discussed above, or the fact that Burnell was a student when the pulsar was first observed, but none of these factors reduce her role in the discovery. During this time, Burnell spoke graciously and even defended the committee’s decision in earlier years. Fortunately, she did receive well-deserved recognition later in her life. Burnell was awarded the Breakthrough Prize for her crucial pulsar work, as well as her teaching and leadership in her field. Once deemed unworthy of the Nobel, Burnell now stands in the good company of Stephen Hawking, who was awarded the Breakthrough Prize in 2013. These are perhaps signs of times changing for the better. In a generous gesture, Burnell donated the Prize money ($3 million) to fund women, under-represented ethnic minorities, and refugee students to become physics researchers. In doing so, she said, "Those are the people that tend to be discriminated against through unconscious bias so I think that's maybe one of the reasons why there aren't so many." She also went on to say, “Nobel Prizes rarely go to young people; they more often go to established people and it's at that level that there are fewer women in physics." This reflects her own past experience of being left out of the Nobel in 1974. Even in her diplomacy, she raised the critical issues of our time - the gender bias and age discrimination. The Structural Issues: The continuing gender gap over the last 100 years of Nobel history must be used to learn and move forward, rather than point fingers. First, it must be the responsibility of both men and women to work on this issue, and all of us must embrace and affect structural changes. Reportedly, Goran Hansson, the permanent secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (RSAS) admitted, “We are disappointed, looking in a larger perspective, that there aren’t more women who’ve been awarded.” In a somewhat contradictory statement, he insisted that, “there is not any substantial male chauvinism bias in the committees.” We have no reason to doubt his motives. However, reviewing the RSAS website, each Nobel Committee for Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine for 2018 includes 6 members of which 5 are men. Admittedly, having more women on the committee does not guarantee, nor should it, that more women will be awarded the Nobel based on gender alone, but this imbalance is a symptom of larger structural issues. A recent study surveyed 63 academies around the world and found that they consisted of only 12% women on average. The FAS, which blocked Curie’s membership in 1910, has only ~8% women and RSAS, with over 600 Swedish and foreign members, has only ~13% women. Equally notable is that RSAS members vote to decide the Nobel Prize recipients in physics, chemistry, and economics each October. The U.S. National Academy of Science also only has ~13% women. These numbers beg the question - is this not a clear case of structural and global gender imbalance in the sciences? The Recommendations: Little may change if we do nothing, but a lot can happen if we make concerted efforts in the nomination process. It is conceivable that at least one woman could receive the Nobel Prize each year in PCM. This is in part because of the increasingtrend in which the science Prizes are shared by three people (meaning a possible 9 winners each year). The recommended action items include: 1. The process of reducing the gender gap must be actively owned and tackled by the scientific community at all levels everywhere, irrespective of individuals’ own gender. 2. While the list of eligible nominators is not easily accessible without due diligence, the most obvious nominators are the current Nobel Laureates in the discipline. Ideally, the respective Nobel Committees must announce the list of eligible nominators each year before the due date for nominations. 3. All scientists must proactively recommend women scientists to Nobel Laureates in the discipline, indicating why they deserve to be nominated for the Nobel. The nominators can nominate more than one individual and a nominee can be nominated by multiple nominators. My belief is that the greater the number of nominations, the better the chance of attracting the committee’s attention. Quality is very critical, but quantity is valuable too. 4. All Nobel committees should include a fair and equitable number of men and women. Likewise, the academies worldwide, with an average of 12% women, must improve the gender ratio of their membership. The RSAS members are eligible nominators too; thus, the science community can submit the names of exemplary women to them for the Nobel Prize. Concluding Thoughts: Obviously, we cannot reward those “missing” women with the Nobel Prize that they deserved, but together we can create a better Nobel history from now on. It would not be unthinkable, with fair representation based on merit, to recognize ~100 Nobel women scientists by 2100. It will necessitate that we nominate the most deserving scientists, and that the deciders in Sweden judge worthiness without bias. As we recognize more women scientists, we will also acquire more role models to inspire, attract, and retain women in STEM. Up until this year, the field of physics had no living women Nobel winners and chemistry could claim one, while medicine has a slightly more respectable score of seven Nobel prizes held by women. Thankfully, 2018 has allowed us to make a move in the right direction, although we do need many more. With numerous gender-based issues raging across media, entertainment, politics, and technology in the United States and elsewhere, the science community needs its own specific “#Me Too” movement. We must bring greater recognition towards the fact that all types of gender bias - the unconscious, unrecognized, unspoken, unwanted, and/or unintended- is totally unwarranted. Collectively, we must resolve that no more women be overlooked in history and lose their right to be duly recognized for breakthroughs that affect all of our lives.

About the Author

A physicist turned Nobel Prize historian, Agarwal has served as faculty and held different academic leadership positions. He spent a year in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and another year as a Fellow of American Council on Education. He lives in Minnesota and runs a non-profit, Vidya Gyan (Vidya is education and Gyan is knowledge) dedicated to education and health of underprivileged children in rural India. He is considering writing a book focused on gender, geography, and the generational journey of physics Nobel Laureates. He would welcome readers’ comments and can be reached by email at [email protected] Comments? Leave them below!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2022

CategoriesAll Amy Massack BiWeekly Roundup Danae Dodge Gabrielle-Ann Torre Indulekha Karunakaran Jeesoo Sohn Lauren Koenig Lidiya Angelova Melissa Bendayan Microsoft Molly Connell Nektaria Riso Nicole Hellessey Physics Poornima Peiris Robbin Koenig Sadaf Atarod Sarah Smith Shreya Challa Vijendra Agarwal Women In STEM Yolanda Lannquist |

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed