|

10/24/2017

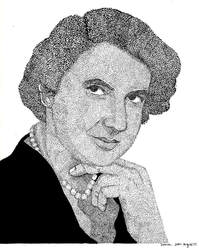

The Unsung Mother of Double Helix

By Iqra Naveed and Muhammad Hamza Waseem

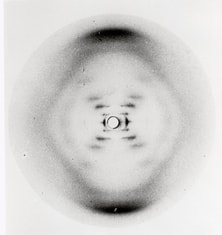

The annals of science bring home the undeniable fact that many scientists have been robbed of the recognition they deserved. The female scientists perhaps have suffered the most because of a male dominant academic culture. Few scientists have suffered more famously than Rosalind Franklin. Many people do not even know about her contribution to science. This is because most textbooks fail to mention her name when discussing the most important discovery of all time, the double helix structure of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) that holds the code of life, and hailing it as synonymous to the celebrated Watson and Crick. Born in 1920 in London, Franklin showed an immense interest in science from an early age. She was the brightest pebble on the beach, always excelling in academics and sports. It was a time when the academic culture was hostile to women, who were not considered to participate in any of the scientific activities. There are mixed opinions on the family support that Rosalind had received for her scientific endeavors. Anne Sayre, a close friend of Rosalind and author of the book “Rosalind Franklin and DNA”, claims that she was discouraged from pursuing science by her father who wanted her to become a social worker. Later, Rosalind’s younger sister Jenifer Glynn denied all these myths, saying that their father always supported her career. Nevertheless, in 1938, Franklin won a scholarship to study chemistry at Cambridge where she ended up getting a doctorate eventually. Franklin moved to Paris in 1947 and at Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'Etat (Central State Laboratory for Chemical Services) perfected her skills in X-ray crystallography, studying coal. This move became her trump card in the work that was to follow. The year 1951 saw her joining King’s College London where she started working on the structure of DNA using X-ray diffraction techniques. Franklin was appointed as a research associate to work with Maurice Wilkins, who endeavored to solve the structure of DNA. But there was a bad chemistry between Wilkins and Franklin from the start. It was partly because of Franklin’s combative nature, but mostly because of Wilkins assuming her to be a technical assistant rather than a researcher as himself. This is testified by the fact that women at that time were not considered to work as peers with men in the lab. Meanwhile, James Watson and Francis Crick were also working passionately on the DNA in the Cavendish Lab at the Cambridge University. They both made incorrect guesses regarding the DNA structure, which Rosalind also declined as wrong. Franklin worked with her assistant Raymond Gosling and, in 1952, produced a clear image of DNA, called “Photograph 51”, which clearly hinted at its double-helix structure with phosphates on the inside. The image took 100 hours to produce and took a year to be analyzed. Watson and Crick managed to publish their work with correct DNA structure in 1953. But there are speculations about how they got the structure right. It is said that Watson and Crick got their hands on the DNA information, which was actually Rosalind’s work. It is believed that Wilkins showed Photo 51 to Watson and Crick without Franklin’s permission. Nevertheless, it is of extreme disrespect to scientists to use their data without their consent. Watson and Crick would have never reached their goal of finding the exact structure of DNA if it were not for Franklin’s data. Afterwards, they made necessary calculations about the helical dimensions and published their paper in the journal Nature, in April 1953. Rosalind also completed her research but her article was published last, making it seem like a quantitative confirmation of the former. In their article, Watson and Crick made an intentionally oblique reference to Franklin’s work, but made it seem like the core discovery was their own backbreaking work. Watson and Crick won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Franklin would never know that it was her data they worked on. No justice was given to her regarding her achievement on DNA. She was the actual deserver of Nobel Prize, but James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins took all the limelight. Apart from her remarkable work on DNA, Franklin also studied molecular structure of coal and how its permeability changed with heat. This eventually led to better gas masks which proved useful during World War 2. Later, she made incredible contributions to the study of polio and tobacco mosaic virus. She was perfectly capable of explaining her work and she was a fighter. Yet she was betrayed not only by her colleagues but also by her short life. Franklin died on April 16, 1958 due to ovarian cancer. Her life was tragically cut short probably because of exposure to high levels of X-ray radiations at work. Her sister Jenifer Glynn says that people often ask her what she would have achieved if she were not a woman. She thinks that the right question is what she would have achieved if she had not died at 37. James Watson later wrote a book called “The Double Helix” in which he described Rosalind as “belligerent, emotional and unable to interpret her own data”. He even criticized her fashion sense and hairstyle. It was easy to target women at that time when there was no feminist movement going and sexism prevailed in the 20th century. Her family got so hurt by his remarks that her mother wanted the world to forget her completely rather than remembering her as a person falsely depicted by Watson. In 2004, The Chicago Medical School founded in 1912, was renamed as “Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science” in honor of her work. It is true that bias against female scientists is less conspicuous nowadays, but it has not been completely eradicated. Even after 59 years of her untimely death, her achievements are still underestimated and no proper recognition has been given to her. To accelerate innovation, scientists should work collaboratively and develop team spirit rather than focusing on their own personal achievements. It is time to give credit to the legendary woman who made significant contributions to the study of molecular structure of DNA, coal, graphite and viruses with her distinctive mind. Above all, it is time to let science serve as a grand equalizer in a society that has long been afflicted by sexism, prejudice and discrimination.

About the Author: Iqra Naveed

Iqra Naveed is a sophomore in computer engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore. She has recently developed interest in science communication and aims at bridging the gap between science and art. She is interested in undertaking science-art projects. Her hobbies include painting, sketching, reading and playing the guitar.

About the Author: Muhammad Hamza Waseem

Muhammad Hamza Waseem is in junior year of electrical engineering at the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore. He is interested in modern physics, optics and physics education. He is actively involved in science outreach and heads the Research and Innovation team of the Science Society at his university. He kills his free time reading classics of English literature and popular science. Comments? Leave them below! |

Archives

February 2023

DiscovHER BlogScientista DiscovHER is a blog dedicated to discovHERies made by women in science. Follow us for links to the latest resHERch! Categories

All Alexandra Brumberg Amy Chan Avneet Soin Chemistry Diana Crow Engineering Health/medicine Indulekha Karunakaran Iqra Naveed Johanna Weker Lidiya Angelova Michael Clausen Mind Brain And Behavior Muhammad Hamza Waseem Nikarika Vattikonda Opinion Prishita Maheshwari-Aplin Technology Uma Chandrasekaran |

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed