|

By Amy Chan

We are all faced with medical evidence – the scientific evidence regarding the use and effect of medication – at some point in our lives. When we visit the doctor and we’re told to start Medicine X because it will reduce the risk of Y, we are being given information deduced from medical evidence. Yet a report from the Academy of Medical Sciences published last month has found that two out of three people don't trust medical evidence, with the same number preferring to trust information from friends and families. With medicines being one of the most common healthcare treatments used, why do so many people distrust medical evidence?

To understand some of the reasons why, let’s look at the pathway of medical evidence from generation to use in practice.

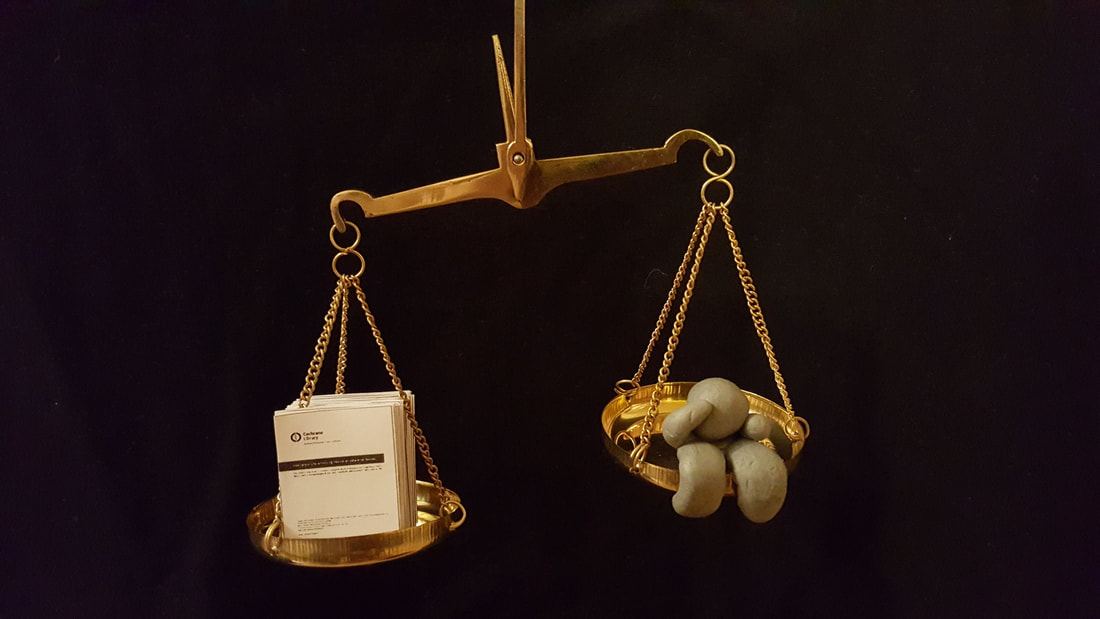

“Weight of Evidence,” artwork by Amy Chan, depicts the ‘burden of evidence,’ with human decision represented on one side of the scales and a miniature Cochrane review on the other The origin of medical evidence and mistrust Evidence for the efficacy of medications comes about from rigorous scientific research, a process which is governed by a set of strict rules and regulations. Yet medical research has been fraught with high-profile scandals in the last decade, which have shaken public trust in medical evidence. Reports of biased results in some industry-funded studies, such as the Rofecoxib and Paroxetine debacles, have fuelled scepticism towards scientific studies as a whole. With industry funding remaining the most common source of funding for medicine trials, and the continued poor public perception of the pharmaceutical industry, it might come as no surprise that the public feel that medical evidence is not to be trusted. While industry funded trials have been the most visible offenders, reports of biased or falsified evidence have been found elsewhere. As seen in the cases of the MMR scare and the Boldt scandal, the risk of falsified results is not limited to industry. The numbers show, however, that these infractions are few and far between. Every year over 2 million scientific articles are published and many funding agencies, especially federal and academic sources, have little to gain financially from one result over another. Certainly, just because some studies have been biased or fraudulent doesn’t mean all research should be distrusted. Why is it then that we continue to distrust medical evidence? Part of this may be due to how our brains our hardwired. We are much more likely to remember bad news and scandals than good news. Our memories recall the negative news better – a mechanism we have evolved to protect ourselves. Distrusting medical evidence can also be seen as evolutionarily protective because having incorrect medical evidence can have life-threatening consequences. Because our brains assess that the risk does not outweigh the reward, we become hyper-critical of the available evidence as an extra precaution. There is also the effect of uncertainty – as we don’t know which studies will have biased results, our minds respond by not trusting evidence in general. The communication of medical evidence New medical evidence is usually communicated first to health providers and researchers, before making its way to the public. The evidence is usually written with health workers or researchers in mind, rather than the public, making it difficult for most of us to understand much of the terminology used. Most evidence is published in academic journals which are not easily accessible. These barriers further influence our trust in medical evidence, as there is a lack of information about how evidence around pharmaceutical treatments is found. Too often we are just presented with a fact or statistic about the medicine – “taking aspirin every day can help prevent a heart attack” without being told how or where this information comes from. This lack of information creates uncertainty and again affects our trust in the information presented to us. Interestingly, this uncertainty around medical evidence may have a greater effect in women, which may explain why women are increasingly turning to ‘wellness therapy’ and alternative treatments. Women have consistently been under-represented in medical evidence, with the male body being considered the ‘default’ in clinical trials. With this gender imbalance, women may find it more difficult to relate to and trust medical evidence; after all, they are not even represented in the evidence in the first place. Use of medical evidence in practice Most of us receive medical evidence when we visit a health provider. Why is it that two-thirds of people would rather trust friends or family than medical evidence and healthcare professionals? There are several factors at play. First, psychology tells us that we are more likely to value the opinions of those that we perceive as similar to ourselves. This effect is also found in doctor-patient relationships – patients who shared the same ethnicity as their general practitioner were more satisfied with their doctor. Secondly, the way we get information from our friends or families is likely to be in the form of stories told based on their experiences. A recent review found that narrative information influenced decision-making more than providing statistically based information. Lastly, the information we currently get through patient information leaflets, has been described as ‘impenetrable’ and ‘unreadable’ to the layperson. This difficulty with understanding medical information further adds to lack of trust in healthcare providers and medical evidence. What can we do about mistrust? Distrust of medical evidence is due to factors found at all levels of healthcare, from medical research to the information shared between health professionals and patients. This distrust arises from poor management of conflicts of interest, a lack of research transparency, and ineffective communication of medical evidence. To tackle this information breakdown, everyone involved in the medical evidence pathway – from researchers to clinicians to patients – needs to take responsibility. Efforts to make research data publically available and to publicly disclose conflicts of interest are important first steps to continue improving the global standard of living with modern medicine. Relationships between researchers, the public, and patients need to be protected and nurtured if we are to make the best use of medical evidence. In this era of fake news and echo chambers, simply creating and sharing medical evidence is not enough – we must all do the utmost we can to ensure we can trust it.

About the Author

Amy Chan is currently a Research Associate with the Centre of Behavioral Medicine, University College London. Her research interests are in medication adherence, health behaviors and beliefs – understanding how and why people behave differently towards different treatments and healthcare. She is also enthusiastic about exploring how technology influences health and healthcare. Her journey through research and her work with patients has opened her eyes to the exciting world of science and clinical research, through which the work of some can help change the lives of many. She believes that "we are only people through people" and that with science and innovation, people are brought closer to each other. She is passionate about communicating science in a way that everyone can understand and aspires to be an effective science communicator. In her spare time, Amy enjoys designing, crafting, exploring new places and is a part of a UK dance company. Comments? Leave them below!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

LIFESTYLE BLOGRead our lifestyle advice, written exclusively for pre-professional women in science and engineering. From advice about fashion, work and family balance, self, wellness, and money, we've got you covered! |

The Scientista Foundation, Inc. All Rights Reserved © 2011-2021 | Based in NY | [email protected]

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!