|

8/16/2011 0 Comments Never Blame the Customer The delay in posting comes from both a need to brainstorm for a topic I find interesting and lack of internet connection. Clearly, both problems have been fixed. The former was fixed when I happened to be in a shoe store at the right time. I overheard (I eavesdropped, but it was for the sake of my blog) an argument between a customer and the store's manager (though he also said it was his first day on the job...). The elderly customer had ordered shoes for her swollen legs months ago, only to find out that the store ordered what was clearly the wrong size (only her toes fit into the shoe). She explained that she had been fitted after trying on many shoes and there was no way that the person helping her could have ordered the size that they did after an hour of shoe shopping. To my utter disappointment, the manager began to defend not the customer, but his own employee, stating (actually it was almost like yelling) that his employee would not do such a thing. Not only would I not recommend this shoe store to anyone (but for the sake of the store, I won't name it here), but I would also say that the first rule of customer service is and should always be: don't blame the customer! Perhaps it was the customer's fault, or maybe it was actually the fault of the employee, or maybe of the warehouse that shipped the shoe...there are so many variables. But when it comes down to it, the buck stops with the store, not with the customer relying on the store for efficient, competent, and most importantly courteous service. Now, I can assure you that as I stood in the store pretending to mind my own business, I was not only infuriated on the inside, but also had an instant light bulb for this blog post. The connection may seem weak at best, so let me clarify. Consider the patient as the customer and the doctor/nurses/hospital as the store. A handful of the patients I saw this summer were small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients. Small cell is perhaps the most aggressive form of lung cancer, and almost always occurs in smokers. It responds very well to initial treatment--almost cruelly tricking the patient and his/her family--because unfortunately, it usually recurs a short period of time later. A logical question of SCLC patients is, "If I hadn't smoked, or if I had quit earlier, could I have prevented my disease?" While the conventional wisdom of a medical oncologist specializing in lung cancer may say yes, the honest answer is: who really knows? Nothing says that a nonsmoker can't have SCLC, as proven by a 2006 article in Nature. No one deserves to have cancer, and just because the patient is a smoker, doesn't mean it's his/her fault that they got such a terrible disease. One may argue that sources such as Harvard Medical School cite that 85-90% of patients who die from cancer are smokers. But the article goes on to say that 15,000 nonsmokers die from the lung cancer annually. Scientists (including the ones I worked with) are eager to continue to learn more about the differences in cancer biology between smokers and nonsmokers. But even so, no doctor has a crystal ball. As the Nature article points out, you can still have SCLC if you don't smoke. The bottom line is, smoker or not, the patient cannot be blamed for his/her disease. The best option is to let go of past regrets that could hinder the patient's attitude (and we've seen that attitude is important), and to treat the patient as best as possible. Maybe a lung cancer specialist should give that shoe store a lesson on customer service. 1. http://www.health.harvard.edu/fhg/updates/Lung-cancer-not-just-for-smokers.shtml 2. http://www.nature.com/nrclinonc/journal/v3/n7/full/ncponc0534.html

0 Comments

8/4/2011 0 Comments No Such Thing as "Game Over"One of the first statistics that most people hear about lung cancer is that it is the deadliest type of cancer with an especially discouraging prognosis: on average, only 15% of patients live to tell the tale five years later. (1,2).

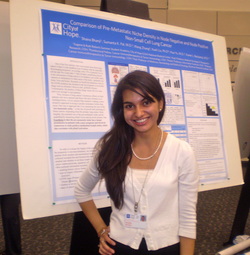

* * * During my time spent conducting research and seeing patients, I've not only learned that lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death, but I've also seen why; the reason comprises of a number of factors, one of which is likely metastasis to the brain, liver and bones. Our research project, entitled Comparison of Pre-Metastatic Niche Density in Node Negative and Node Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, was, in the most general terms, an effort to find a way to predict metastases before they occur. For those who would like some more tangible science to grasp on to, we collected data on 60 patients (smokers and nonsmokers) to see if they had benign lymph nodes available and then looked to see whether they had any involved (cancerous) lymph nodes...the goal being to see if CD68 (a glycoprotein on myeloid cells) and pSTAT3 (a transcription factor important in programmed cell death) could be used as markers to determine the prominence of a pre-metastatic niche. The pmn is an idea (much like that of the stem cell niche) that there is a hub where cancer cells grow and eventually metastasize. After more than eight weeks of looking through medical records to collect data from pathology and operative reports, it was finally time to analyze the data. As I anxiously looked at the results, I was honestly shocked when we didn't find what we expected. That being said, a lot of our current data is censored, because some information is still being collected. So we may eventually see some correlation between our markers and nodal stage (a measure of how much cancer has spread to the lymph nodes of the chest, and which specific nodes). My point is that more often than not scientists don't find what they're looking for or what they expected. But that's the beauty of it. If a child always got what he or she wanted, the child would be spoiled just as if scientists always found what they were looking for, I believe they'd become complacent. Just because you don't find what you expected doesn't mean you didn't find anything at all. As my mentor pointed out, there's always a positive spin on what you did find, and it pushes you to take a different approach to your question. Shocked as I may have been, I've learned there's no such thing as "game over" when it comes to science. 1. "Cancer of the Lung and Bronchus - SEER Stat Fact Sheets." Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. National Cancer Institute & U.S. National Institutes of Health. Web. 06 July 2011. <http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html>. 2. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al: Cancer Statistics, 2009. CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 59:225-249, 2009. 7/28/2011 0 Comments Remember Your Passions In the rush of the school year and the jumble of the sometimes mundane pre-med classes, it's easy to forget the end goal. It's easy to forget that there is more to life than the tiny details of biology and chemistry that I may never remember. If there's no one pulling you back to the big picture, it's easy to miss the real-world applications of the concepts taught in general education chemistry and biology classes. The practical applications that interest me most about medicine (examples: targeted HIV therapies or beneficial mutations in lung cancer patients) are often lost in minutiae, (unnecessary?) stress, and the pressure of needing to thrive. But these classes are all just particles of a bigger galaxy.

I relayed my frustrations to my mentor in one of our final meetings. I guess I have this notion that because I'm doing an internship at such a prestigious institution, I have a duty to be overly zealous about every aspect of biology and chemistry - especially if I want to be a doctor. No surprise, I'm wrong again. My mentor gave me a much-needed reality check. She said (I'm paraphrasing), "You'll always have to do things you don't like. But, if you can remember the end goal, and remember what it is that really excites you, that will keep you going. You have to remember your passions." I guess I knew this in my heart all along, but I needed to hear it from someone I look up to and respect, because hearing it from my conscience clearly does me no good. More importantly, I've realized that there's more to medicine than being a doctor. This seems like a simple realization, but put yourself in the shoes of someone who has wanted to be a doctor her whole life. Coming to the conclusion that maybe an M.D. could be for me, or maybe I'm more interested in global health and the economics of health-care has been refreshing and eye-opening, but also one of my most difficult realizations in a long time. She is a middle-aged woman whose name (though I can't say it here), describes her perfectly: jolly, upbeat, and full of love. I remember the first time I met her: she was wearing a mask over her mouth, but her smile shined right through it. As I smiled, watching her give the nurse practitioner a hug and even a kiss on the cheek, I was caught off guard as she reached out to do the same to me. I continued to smile, even as she talked about the symptoms she was having, because she was happy despite what she was facing. I'm no doctor or psychologist, but I do believe that her bubbly attitude played a role in the improvement of her condition. My mentor once explained to me that pain is part physical and part psychological. I am a firm believer that a patient's battle against cancer depends as much on their treatment as it does on their spirit. So as we got ready to leave, I was ready for my hug and kiss. Apparently I was a little too ready, because the patient laughed, reaching out to me and saying something to the effect, "Oh honey, you know the drill!" I know I shouldn't have favorite patients, but I do, and she's it.

* * * He is a tall, well-built, older (but not old) man. I remember him as the Stanford grad, because I can never remember his name. He is taking a drug called Tarceva (erlotinib), which has been shown to be especially beneficial for patients with a mutation called the EGFR mutation. Amongst the drug's symptoms are dryness--of the skin, mouth, eyes, and just about every other body part. This man has a most painful looking rash all over his face and upper body, like red burning scales. Just looking at it makes my teenage acne seem like a joke. The rash is like a summer brush fire on his skin. It is so painful that he cannot put anything on it except a wet towel--not even lotion of any kind--and he sleeps with a fan on his body at night. Every time I see him, I fail to imagine how uncomfortable he is. A simple bug bite drives me crazy--and there are anti-itch creams for that. This is one example of the endurance that cancer patients have. Where they get it from I do not know, but I wonder how I would hold up if I were in their shoes. * * * What I remember most about this elderly patient is her family, specifically her daughter and son-in-law. The first time I met them, I listened to the nurse practitioner try to give what we call a "hospice talk." As a side note, hospice is usually associated with death.It is suggested as an option for patients who will be needing extra care at home as their condition deteriorates. They may become too weak to come in for regular checkups in clinic, in which case hospice nurses and doctors will provide them with care at home--specifically with symptom control so that the patient can maintain his or her quality of life as much as possible. The goal is to make sure the last days are not wasted. Given the subject's negative connotations, it is no surprise that when the NP or doctor suggests a patient consider hospice care, sometimes the response is not pleasant. In this case, the patient's family became subtly defensive, explaining that they came to City of Hope for an ounce of hope. Understandably so. But what they said next is what I'll never forget (I'm paraphrasing). "Give her anything, even if it's not chemo, even if it's just water. Just give her something." For some patients, hope means treatment, shoving something into the patient's veins even if it will do them no good--or worse, it may actually do them harm. I've been told time and again that the first rule is to do no harm. So as soon as symptoms from treatment begin to ruin a patient's quality of life in attempt to enlarge the quantity, this line has been crossed, and it's time to weigh the scales. She was a young woman. Beautiful, no doubt--regardless of the fact that her battle had made her as skinny as a twig. I remember thinking how posh she looked, with her unnaturally perfect brunette bob and her killer black pointed flats. She had a teenager without a father. More pressingly, however, she had cancer--and it had spread. Her battle started as a child with lymphoma, and like a recurring nightmare, it had come to haunt her again in her lungs and liver. But I would not get to admire her fashion sense again, because the next time I would hear about her just a few days later....

would be when she was dead. Albeit this patient passed away from other complications (in other words, her cancer did not sneak up and grab her suddenly in the middle of the night), the case for me serves as a metaphor for how unpredictable cancer is. More literally, it served as a wake-up call. As terrible as it may sound, this case is what it took for to me to register in my mind what these patients are really up against. A couple weeks earlier, I sat down for a chat with my mentor. It was one of our meetings together that particularly stands out. She described the difficulty of not taking the "baggage" out of the room--in other words, not feeling personally responsible for the fact that most of (certainly not all, as we like to believe that miracles can and do happen) these patients will ultimately die as a result of their disease. In fact, I was having the opposite problem. I had no feeling of baggage as I left the room, nor was I emotional (unless the patient was emotional; I guess I suffer from sympathy pains). While some may argue that aloofness is an important trait for a future doctor, I was disturbed. Am I heartless? Why can't I bring myself to understand that these people are dying? But when the above patient passed away, all of the naïveté that I brought with me to the job disappeared. I guess I never really believed that these people would actually die--at least not within the ten short weeks I was there. Like a little girl holding on to her beliefs in the existence of the tooth fairy, the notion that everyone is a good person, and the fairytale that the world is a fair place, I held on to my hopes that these people would not die. I built a wall between myself and the fact that they would die so I would not have to acknowledge it. But my wall came crumbling down pretty hard. I guess I've gone on a major tangent, but maybe it's not so big. A day in the life...well, to be honest, there's no one day that describes all days. We're up against something different everyday. As my mentor pointed out, two lung cancer patients could be the same age and stage, and yet their stories are likely completely different. So on the days that I'm in clinic (Mondays and Wednesdays; the other days I work on my data collection project described in the first post--which is also very fulfilling), it's impossible for me to tell how the day will go. Every patient is different, and every family is different. Some take bad news better than others. On the other hand, some need to be told to be "thrilled" at good news. As I watch my mentor in the room with patients, I am amazed at how calmly she lets emotions flow. This goes back to another one of our meetings together when she described to me how she has learned, over the years, to let this emotion flow. To paraphrase her, it's important to let patients and family feel what they need to feel. The anger, raised voices, tears, and yes, sometimes, name-calling cannot be taken personally, because they are not meant to be. Everyone has different coping methods. In the case of bad news, it's a hard thing to do, to sit with a white coat on and face, with wide eyes, the patient and family who often have a subconscious perception of you as the "angel in the white coat." But doctors don't have angelic powers; they're just people. 7/13/2011 0 Comments A Time for IntroductionsI recently attended a talk by Sandra Tsing Loh, a Caltech physics major who is now an accomplished author, comedian, and radio commentator (amongst other talents). I was fascinated to hear of her own process of trial and error as she searched for her true passion. She graduated from Caltech with a B.S. in physics and sat for the GREs only to realize mid-exam that physics was not her true passion. How fitting it was that she should be addressing an audience of young students who are struggling to find out exactly who they want to be, though many of them had a vague idea they would like to pursue science. Science, much like life itself, is a process of trial and error with the aim of bringing out the best--whether it be from within a test tube or an individual.

I first experienced this trial and error last summer--my first summer conducting lab research. I was that lab rat making all sorts of concoctions (the wrong ones, on more than one occasion). Unlike last summer, this summer I am in a "dry lab," or what some people would not really consider a lab at all. Lab or no lab, however, the research I have been doing has been fulfilling, inspiring, and eye-opening. To say the least, this summer is one that I am certain I will never forget. Right now you're probably thinking to yourself, "Yeah yeah. That all sounds so cliche." You're right. It does sound cliche. But, it's true--and I hope you will begin to see why. More specifically, I have been doing lung cancer research at the City of Hope (COH) National Medical Center in Duarte, California (getting my year's worth of vitamin D before heading back east). As a comprehensive cancer center, City of Hope couldn't have a more fitting name. Part of COH's job is to instill patients with a sense of hope, and many times this is one of the primary reasons patients want to be treated at COH. There is no hope without new knowledge. As such, COH combines breakthrough research leading to clinical trials with a treatment hospital, so the patients are at the forefront of new treatment discoveries that they can benefit from. I am doing data collection to examine the results of an ongoing clinical trial. Specifically, we are examining whether certain lung cancer patients who have lymph nodes that are "involved" (positive for lung cancer) are more predisposed to the formation of a larger "pre-metastatic niche," or a womb of sorts for developing cancer cells that results in metastases. If the answer is yes, then researchers may be able to predict the formation of secondary tumors in patients before they happen. Anyone who knows anything about cancer knows that planning and early detection is crucial. This is especially true in lung cancer, where patients present with few symptoms in early stages, and the cancer is usually not able to be detected until after it has spread. I also have been working on a clinical trial with a doctor, whom I am so fortunate to have as my mentor. This enables me to see patients, whose stories are what have impacted me most. I hope that I can convey the meaning that these experiences hold for me in this blog. Due to patient privacy rules, there are some details (age, name, personal identifying features) that I cannot reveal. However, I am sure that the sheer power of these stories is strong enough such that it will not be lost. |

City of Hope National Medical Center Internship

|

The Scientista Foundation, Inc. All Rights Reserved © 2011-2021 | Based in NY | [email protected]

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

The Network for Pre-Professional Women in Science and Engineering

The Scientista Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) -- Donate!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed